"Water

water see the water flow

glancing dancing see the water flow

o wizard of changes water water water

dark or silvery mother of life

water water holy mystery - heaven's daughter

god made a song when the world was new

water's laughter sings it true

o wizard of changes, teach me the lesson of flowing"

©1968 The Incredible String Band

A book I recommend

to anyone interested in the history of water diversion in Hawaii

is Sugar Water: Hawaii's Plantation Ditches

by Carol Wilcox: © 1996 published by University of Hawaii Press

[ISBN 0-8248-1783-4]. Here are a few quotes...

"The

Hawaiian subsistence economy was based on taro production. Taro

was the staple of the hawaiian diet and at the core of its culture

and religion. The work it took to grow taro, to develop and maintain

the irrigation systems and terraces known as "lo`i", was

shared by the entire community."

later,in reference

to the time after the plantations had diverted much of the valley

water on the island, the book speaks of the impact...

"A

degree of despair, fatalism, and chaos must have characterized those

times. Large numbers of Hawaiians left their traditional homes in

the rural areas. By the time of sugar's ascendancy, when the large

water projects were diverting water away from the valleys and their

villages, these villages did not have the population, organization,

or will to protest."

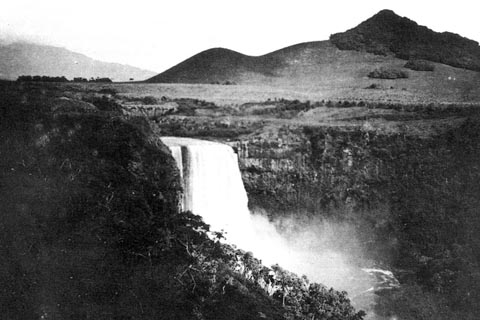

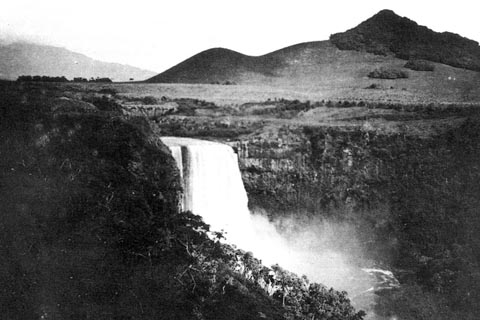

Wailua Falls

in 1908 before Lihue Plantation reduced it to a fraction of its

natural flow.

The book, Sugar

Water, goes on to detail the history of the construction

of ditches, tunnels and reservoirs throughout Hawaii. Here is another

quote in reference to Kauai.

"If

there is such a thing as too much success, the Koula Tunnel is surely

an example. For many decades, both upstream user Makaweli Plantation

(now Gay & Robinson) and downstream user McBryde Sugar between

them diverted essentially all the water from the Hanapepe River,

so that the mouth of the river was usually dry."

One thing is

clear, the way the plantations engineered their water diversion

projects was to take all the water they wanted and let the overflow

go back to its natural course. Often there was no overflow. Typically,

all of a stream's flow was diverted and a spillway was created over

which "excess" water flowed back to the original streambed.

This is how water in the lower portion of the Hanapepe River is

taken to feed the Kauai Coffee Company fields (once McBryde Sugar).

There is a spillway

on the Hanapepe River (right below the end of the cliff when viewed

from the Kamalii Highway Hanapepe Valley Lookout) that diverts the

entire Hanapepe River into private hands. Usuualy so much water

is taken upstream that the river water never crests the spillway.

The only water returned to the river at this location is a small

break in the concrete spillway that an adult can step over that

permits a rivulet of water to escape. Today, the Hanapepe River

is a shadow of its former self.

This is ass-backwards.

This was demonstrated in 2000 when the Hawaiian Supreme Court ruled

that diverted waters on Oahu should be returned to their natural

streambeds and that the public and environmental concerns would

supercede the historic private agricultural interests.

It is clear

that our valleys are the source of life's diversity on these islands.

It is time that the state compel the private business interests

that monopolize water today put in place new management priorities.

Where and if necessary this may require the re-engineering or even

dismantling of water diversion systems to ensure that our valleys

are healthy.

PARTING

THE WATERS

If a tree falls in the forest, and no one hears it, does it

make a sound? And if a stream flows through a valley and into the

sea, and no one uses it, is it wasted water?

The Hawaii Supreme Court hasn't actually heard arguments on the

first case. But on Aug. 22, 2000, it handed down a landmark decision

on the latter case, an appeal of the Commission on Water Resource

Management's 1997 decision to reallocate the water collected by

the Waiahole Ditch. For nearly 80 years, the Waiahole Ditch irrigation

system had transported water from the Windward to the Leeward side

of Oahu. In the 1997 decision, approximately 10 million gallons

of water per day (mgd) were reallocated to Windward streams. It

was the most comprehensive assessment of water law and the first

time in state history that diverted water was returned to streams.

The court's judgment answered both questions along with a myriad

other issues that have been in dispute for decades. In the decision,

the court reaffirmed the public trust doctrine and the State Constitution

saying that the “duty to protect public water resources is

a categorical imperative and precondition to all subsequent considerations,

for without such underlying protection the natural environment could,

at some point, be irrevocably harmed.”

“Realistically, if we hadn't been here, the water would have

never been returned,” says Paul Reppun, a Windward farmer

and longtime community activist. “But the Supreme Court's

decision said that even if farmers hadn't been here in Waiahole

with a need for water, there still would be a public interest in

maintaining free-flowing streams and near shore waters.”

BACKGROUND

According to taro farmer and avid fisherman Danny Bishop,

the return of Waiahole water almost immediately improved the health

of Windward Oahu’s near shore waters.

The Waiahole

Ditch irrigation system, constructed from 1913 to 1916, had transported

almost 30 mgd of fresh water from rainy Windward Oahu, through the

Koolau Mountain Range, to the parched Leeward side of the island

and its thirsty sugar cane fields. The diversion of the water fueled

the Islands' economy and shaped Oahu's development for nearly 80

years.

For more than 30 years, Windward farmers and community representatives

petitioned for a return of water to their streams, but it wasn't

until 1993 when the Oahu Sugar Co. announced that it would stop

growing sugar cane that the fight for water got serious. The resulting

litigation involved many of the largest landowners in the state

and nearly every major law firm in Honolulu.

In 1995, attorneys for the various parties involved, hammered out

an interim agreement while the Water Commission decided on the final

allocation. At that time, more than 10 mgd was put back in the Windward

streams, the first time the waters flowed so swiftly in nearly a

century.

According to taro farmer and avid fisherman Danny Bishop, the health

of Waiahole Stream has improved dramatically since the flow was

increased on an interim basis in 1995. Exotic freshwater species

of fish were immediately flushed out, clearing the way for native

fish and snails. In addition, the area's near shore ecosystem was

partially restored, a prime breeding ground for marine life.

“We knew things would improve, but we didn't expect them to

improve this much, this fast,” Bishop says. “Ask any

longtime fisherman around, and he'll tell you about the improvements.

I've never pulled up so many hee (octopus) before. We still have

a lot of problems in Kaneohe Bay, but the return of the water isn't

one of them any more.”

In December 1997, the Water Commission issued a 250-plus page ruling,

increasing the amount of water distributed to Leeward parties by

3.8 mgd. In January 1998, the decision was appealed to the Supreme

Court, and more than two years later, the court issued its historic

ruling.

“For a long time, there was a perception that water flowing

into the ocean was wasted water. The scientists didn't think that

was the case and neither did the people who fished the waters of

Kaneohe Bay, and now the Supreme Court sees the value of free-flowing

streams,” says D. Kapua Sproat, attorney for Earthjustice,

which represented a coalition of community groups and filed the

appeal to the Supreme Court.

In December 2001, the Water Commission issued another decision regarding

Waiahole water. Shortly thereafter, Sproat filed another appeal

to the Supreme Court. While every decision is crucial to the parties

involved, Sproat believes that the long battle for Waiahole water

may be near an end. “I fully expect that after the next decision,

there will be more issues that will be remanded back to the Water

Commission,” Sproat says. “But the initial decision

covered so much ground, I think many of the issues have been settled.”

|