by Jeffrey and Michele Victor

You can give a French touch to your everyday cooking. How? It's easy, nothing mysterious or exotic. Just grow some typical French vegetables in your garden "et voila!"

When we moved to Jamestown many years ago, we were constantly searching the area markets for vegetables which my wife liked to eat and cook in France, and when we started our own garden, the first thing that we decided to plant were those vegetables which are easy to grow locally and are never or seldom found in the local stores. My wife is from Normandy and her family has always had a garden. Nearly everyone in France who can do so, has a small garden; in fact, it takes precedence over a lawn around most homes. Perhaps it is the heritage of years of deprivation during the wars, or perhaps there is a peasant farmer in the heart of all Frenchmen. Whatever the explanation, vegetable gardens sprout from front or back yards of millions of French homes. Apartment dwellers have long sought out a small spot of land in city gardens. Cities and factories parcel out unused land and make it available to employees or residents for gardens. Once issued, they remain in the hands of the same "tenant" for years, this gives the garden tenant enough security to build his garden tool shed there to keep all of his equipment and decorate it with flowers and other ornamentation.

My first gardening interest was spurred when my wife actually decided to bring to her family the unusual food that she discovered here in the form of seeds for them to grow. Our first corn growing experience attracted quite a crowd along the fence of our French relatives when it reached over 6 feet high! The village was asking about the animals for whom no doubt this would be going to. When we explained the it was "people food" they laughed. By the end of August, the entire village was eating corn! The following year, we continued with spaghetti squash.

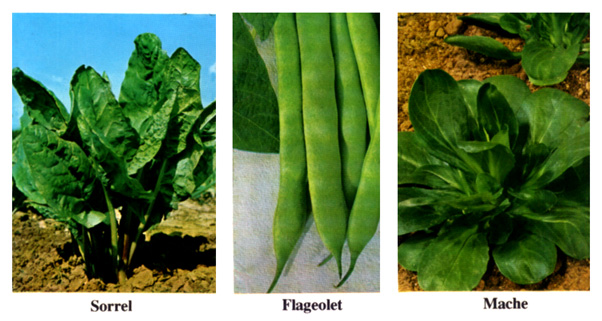

In our first garden in Jamestown, the soil had never been cultivated beyond a sparse lawn and small flower beds, so we started with herbs from France: Thyme from Provence and Sorrel from Normandy. The Jamestown winters are very different from the Normandy winters (planting season starts in February - March there!) so we have to be realistic about what we can grow here. It is quite possible to grow a fairly good amount of what is considered French food here, however, and seed catalogs are featuring more of them.

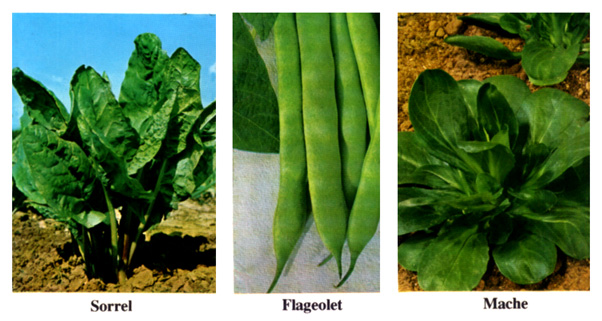

Sorrel grows so well that we keep dividing it and distributing our plants to friends. We also grow flageolet beans, which look just like string beans when fresh, but are eaten dry. We also grow corn salad, sometimes called "Mache". All of these are very well suited for our climate, the corn salad is even incredibly well adjusted to our winters. Both sorrel and corn salad can grow up to the first real hard frost and heavy snow (it can take a light snow or frost, it actually tastes better after a light frost). Dried flageolet beans can be harvested up to October and used all winter.

SORREL

Sorrel is a leafy perennial. There are two main varieties: garden sorrel (Rumex acetosa) and French sorrel (Rumex soutatus). Garden sorrel has elongated, spade-shaped leaves, while French sorrel has broader, heart-shaped leaves. We have grown both varieties and to my taste they are identical. However, gardening books do report that the French variety is less acid. There is a definite difference in the ease of preparation for cooking. The French variety has crispier, less fibrous leaves and they are easier to strip of the center stem at cleaning time.

The tiny seeds can be planted in early spring, as soon as the ground warms up. The seeds take three weeks or longer to germinate and the tiny seedlings grow very slowly at first, as they sink their tap roots deep. I recommend getting them started indoors or in a cold frame. You should have a small crop by the end of the first summer. However, your crop will multiply greatly the second year and endlessly thereafter. You only need five or six plants to provide your family with an abundance of leaves throughout summer and fall.

Actually, the easiest way to grow sorrel is to propagate it from root divisions. (Be careful to dig up as much of the long tap roots as is possible.) We have supplied numerous friends with this new-found delicacy in this manner. Once your patch of sorrel begins to expand too much, it is wise to thin it out. Doing so every few years increases the leafy growth and reduces the amount of woody flower stalks. Also, remember to cut these flower stalks as soon as they emerge in the spring. You may have to keep at it a bit, because the plants are stubbornly persistent in their attempt to go to seed. But it is necessary if you desire your plants to put their energy into growing large healthy leaves.

Sorrel will grow in just about any kind of soil. It was able to do quite well even in our unimproved heavy clay soil where I had transplanted some clumps that I had not given away. Of course, it will prosper best in rich, well-drained soil. Sorrel is very adaptable and can produce in both full sun or partial shade. The seeds are readily available from many companies, but one usually must search for them in the herb section of catalogs.

When picking sorrel for cooking, you should remember that the leaves wilt very rapidly. So, either pick them just before you plan to use them, or keep the leaves in cold water to retain their freshness. Actually, when it looks as if there are plenty of large size leaves ready, we pick them, wash and strip them of their middle stems and spin-dry them in a salad spinner (or shake them in a towel) and keep them in the refrigerator in a ziploc bag until needed (that way, they keep just like spinach). When grown in a large quantity, sorrel can be preserved by cooking it in a small quantity of butter then melted until it looks creamy and freeze it in small containers, to take out from the freezer when needed all winter long. In France sorrel is a favorite for soup. There are many variations of sorrel soup. The one offered in this issue has been my wife's family recipe and seems to be close to most French recipes. Another variation, known as shav soup, is familiar to Eastern Europeans. In this country, it is commonly found bottled on the shelves of metropolitan supermarkets in the Jewish food section. In France, sorrel soup is a favorite of working women because of its fast cooking time.

FLAGEOLET BEANS

The culture of flageolet beans is essentially the same as bush beans. Instead of harvesting the pods, however, you must wait until all the pods have ripened. Then, pull out all the plants and hang them out to dry in the sun for a few days. Afterwards, simply shell the pods to collect the attractive light green beans. These may be used immediately, or they can be dry stored for the winter.

Flageolet beans have been likened to lima beans in appearance and taste. But this comparison cannot do justice to the greater delicacy of taste and texture that one experiences with a meal of flageolet beans. It is not surprising that when Gurney's Seed and Nursery (Yankton, S.D., 57079) introduced them as a "new" vegetable offering, Gurney advertised them as the "Gourmet French bean". The taste is very slightly sweet, with no trace of bitterness. The cellulose seed envelopes are much thinner that those on lima beans. Seeds for flageolet can be obtained from many companies.

CORN SALAD GREENS (MACHE)

Corn salad is a salad green commonly available in the spring in French supermarkets. It ought to be more familiar to Americans because of the special benefits it has to offer garden and kitchen. Corn salad, otherwise known as lamb's lettuce and fetticus in English or mache in French, is easy to grow and thrives with the resistance of a weed in your garden. Indeed, it is a common weed in European wheat ("corn") fields. It is very hardy in cool weather and easily survives hard fall frosts. It has even survived harsh winters in my garden under a blanket of snow, protected by an insulating mulch of straw or leaves. The advantage is clear. You can take fresh salad greens from garden to salad bowl after your lettuce has long since disappeared. I plant the seeds at the end of August or beginning of September to have fresh salad available in November, or even later, an over-winter planting will bring you ready-to-eat mache as soon as winter ends. Corn salad may also be planted in early spring, but it doesn't do well once hot weather commences.

Corn salad is a small plant with spoon-shaped leaves attached to a ground-level stem. In my garden, the leaves reach four to six inches in length, but the leaves can grow twelve inches long in areas with long, cool growing seasons. In my father-in-law's garden in Normandy, it does grow to that size. I have planted two varieties: Big Seed and Cambrai. The latter has smaller, but thicker leaves and is a bit more crunchy and juicy in salads. The flavor of corn salad is similar to mild, butterhead lettuce and the texture is even more buttery, such that the leaves seem to melt in your mouth.

Corn salad is very adaptable, because it can be grown in just about any soil and can take partial shade. However, it does best in light, sandy, well-drained, nitrogen rich soil. Few pests seem to bother it. Even the many slugs in my garden don't seem interested. If you went to try corn salad, seeds can be obtained from many seed companies.

The salad comes last in a traditional French meal, justified by the belief that this arrangement aids digestion and cleanses the palate before desert. A salad of corn salad is traditionally served mixed with a crushed hard-boiled egg and/or diced red beets in a simple oil and vinegar dressing. You can, however, enjoy it plain with a few walnuts and raspberry vinegar and oil.

We are including recipes for Sorrel Soup, Sorrel Sauce, Flageolet Beans and a simple French Dressing for Mache and other lettuce greens. You can then have a typical French family dinner. Don't forget the wine!

|

1/4 cup wine vinegar 3/4 cup vegetable oil a dash of pepper salt to taste Mix and shake until blended, keep unused portion refrigerated. Makes 1 cup of dressing.

|

|

1 cup finely chopped washed sorrel leaves 2 tablespoons butter 1 chopped onion (optional) 1 tablespoon flour 1 quart hot water or chicken stock 1 tablespoon salt 2 diced potatoes 1/4 cup fine soup noodles 1 cup milk or 1 tablespoon heavy cream (optional) Sorrel leaves should be washed and have their middle stem stripped. Dry the leaves for excess moisture and cut in strips. In a heavy soup pot, melt the butter, add the chopped sorrel leaves and stir; and when the leaves appear melted, add onion and stir to mix. Add the flour and mix until smooth. Add the liquid gradually while stirring gently until the mixture is smooth. Bring to a boil and add the potatoes and the salt. Taste. Cover and lower the heat. Cook until potatoes are done (20 minutes). Mix in blender or with hand held blender. Add the noodles. Cook until noodles are soft (10-12 minutes). Milk or cream can be added at serving time. This soup is quick to prepare and always tastes better the next day! Makes 4 servings. Note: Because of the high acidity of the sorrel, do not use an aluminum cooking pot.

|

|

1 cup finely chopped washed sorrel leaves 2 tablespoons butter 1 chopped onion (optional)

Sorrel leaves should be washed and have their middle stem stripped. Dry the leaves for excess moisture and cut in strips. In a heavy soup pot, melt the butter, add the chopped sorrel leaves and stir; and when the leaves appear melted, add onion and stir to mix. This makes the best fish sauce that you will ever have. In France, it is served on salmon steaks or turbot filets. Lemon juice can be added and olive oil can be substituted for the butter. The sauce should have a smooth creamy green consistency.

|

|

2 & 2/3 cups (1 pound) dry flageolet beans 6 cups of salted cold water 1 onion or large shallot, chopped 3 large minced cloves of garlic 1 sprig of thyme 1 bayleaf (optional)

Cook the flageolet beans just like you would cook white dry beans. First wash the beans, then put them into cold water with a tablespoon of baking soda and bring to a boil. Allow to boil for 2 minutes. Strain in a colander. Bring the 6 cups of water to boil in the heavy pot. Add the blanched beans, the onion, the garlic. Cook until tender. It is traditional in France to serve flageolet with leg of lamb or roast beef and to add some of the natural meat gravy on the flageolet at serving time. It is important not to overcook the beans. Cooking time is about 1 hour. Makes 8-10 servings.

|

Editor's Note:

Michele and Jeff Victor live and work in Jamestown, New York. Jeff teaches sociology at Jamestown Community College and is a published author. Michele has taught French at SUNY Fredonia and is a professional French language translator. We know from personal experience the pleasure it is to dine with the two of them.