SUBJECT: CONTRAS & COCAINE

SOURCE: JUAN WILSON juanwilson@mac.com

Kerry started investigation of the drug funded terrorists

24 October 2004 - 5:00pm

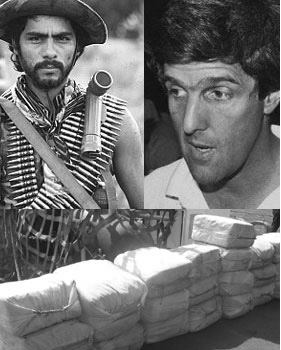

A Contra on the Honduran-Nicaraguan border; Sen. John

Kerry, in 1986; and a seized shipment of cocaine.

How

John Kerry exposed the Contra-cocaine scandal

(excerpted)

by Robert

Parry published in Salon.com 25 October

2004

Derided by the mainstream

press and taking on Reagan at the height of his popularity, the freshman

senator battled to reveal one of America's ugliest foreign policy secrets.

In December 1985, when Brian Barger and I wrote a groundbreaking story

for the Associated Press about Nicaraguan Contra rebels smuggling cocaine

into the United States, one U.S. senator put his political career on

the line to follow up on our disturbing findings. His name was John

Kerry.

Yet, over the past year, even as Kerry's heroism as a young Navy officer

in Vietnam has become a point of controversy, this act of political

courage by a freshman senator has gone virtually unmentioned, even though

-- or perhaps because -- it marked Kerry's first challenge to the Bush

family.

In early 1986, the 42-year-old Massachusetts Democrat stood almost alone

in the U.S. Senate demanding answers about the emerging evidence that

CIA-backed Contras were filling their coffers by collaborating with

drug traffickers then flooding U.S. borders with cocaine from South

America.

Kerry assigned members of his personal Senate staff to pursue the allegations.

He also persuaded the Republican majority on the Senate Foreign Relations

Committee to request information from the Reagan-Bush administration

about the alleged Contra drug traffickers.

In taking on the inquiry, Kerry challenged President Ronald Reagan at

the height of his power, at a time he was calling the Contras the "moral

equals of the Founding Fathers." Kerry's questions represented

a particular embarrassment to Vice President George H.W. Bush, whose

responsibilities included overseeing U.S. drug-interdiction policies.

Kerry took on the investigation though he didn't have much support within

his own party. By 1986, congressional Democrats had little stomach left

for challenging the Reagan-Bush Contra war. Not only had Reagan won

a historic landslide in 1984, amassing a record 54 million votes, but

his conservative allies were targeting individual Democrats viewed as

critical of the Contras fighting to oust Nicaragua's leftist Sandinista

government. Most Washington journalists were backing off, too, for fear

of getting labeled "Sandinista apologists" or worse.

Kerry's probe infuriated Reagan's White House, which was pushing Congress

to restore military funding for the Contras. Some in the administration

also saw Kerry's investigation as a threat to the secrecy surrounding

the Contra supply operation, which was being run illegally by White

House aide Oliver North and members of Bush's vice presidential staff.

Through most of 1986, Kerry's staff inquiry advanced against withering

political fire. His investigators interviewed witnesses in Washington,

contacted Contra sources in Miami and Costa Rica, and tried to make

sense of sometimes convoluted stories of intrigue from the shadowy worlds

of covert warfare and the drug trade.

Kerry's chief Senate staff investigators were Ron Rosenblith, Jonathan

Winer and Dick McCall. Rosenblith, a Massachusetts political strategist

from Kerry's victorious 1984 campaign, braved both political and personal

risks as he traveled to Central America for face-to-face meetings with

witnesses. Winer, a lawyer also from Massachusetts, charted the inquiry's

legal framework and mastered its complex details. McCall, an experienced

congressional staffer, brought Capitol Hill savvy to the investigation.

Behind it all was Kerry, who combined a prosecutor's sense for sniffing

out criminality and a politician's instinct for pushing the limits.

The Kerry whom I met during this period was a complex man who balanced

a rebellious idealism with a determination not to burn his bridges to

the political establishment.

The Reagan administration did everything it could to thwart Kerry's

investigation, including attempting to discredit witnesses, stonewalling

the Senate when it requested evidence and assigning the CIA to monitor

Kerry's probe. But it couldn't stop Kerry and his investigators from

discovering the explosive truth: that the Contra war was permeated with

drug traffickers who gave the Contras money, weapons and equipment in

exchange for help in smuggling cocaine into the United States. Even

more damningly, Kerry found that U.S. government agencies knew about

the Contra-drug connection, but turned a blind eye to the evidence in

order to avoid undermining a top Reagan-Bush foreign policy initiative.

The Reagan administration's tolerance and protection of this dark underbelly

of the Contra war represented one of the most sordid scandals in the

history of U.S. foreign policy. Yet when Kerry's bombshell findings

were released in 1989, they were greeted by the mainstream press with

disdain and disinterest. The New York Times, which had long denigrated

the Contra-drug allegations, buried the story of Kerry's report on its

inside pages, as did the Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times.

For his tireless efforts, Kerry earned a reputation as a reckless investigator.

Newsweek's Conventional Wisdom Watch dubbed Kerry a "randy conspiracy

buff."

But almost a decade later, in 1998, Kerry's trailblazing investigation

was vindicated by the CIA's own inspector general, who found that scores

of Contra operatives were implicated in the cocaine trade and that U.S.

agencies had looked the other way rather than reveal information that

could have embarrassed the Reagan-Bush administration.

Even after the CIA's admissions, the national press corps never fully

corrected its earlier dismissive treatment. That would have meant the

New York Times and other leading publications admitting they had bungled

their coverage of one of the worst scandals of the Reagan-Bush era.

The warm and fuzzy glow that surrounded Ronald Reagan after he left

office also discouraged clarification of the historical record. Taking

a clear-eyed look at crimes inside Reagan's Central American policies

would have required a tough reassessment of the 40th president, which

to this day the media has been unwilling to do. So this formative period

of Kerry's political evolution has remained nearly unknown to the American

electorate.

Two decades later, it's hard to recall the intensity of the administration's

support for the Contras. They were hailed as courageous front-line fighters,

like the Mujahedin in Afghanistan, defending the free world from the

Soviet empire. Reagan famously warned that Nicaragua was only "two

days' driving time from Harlingen, Texas."

Yet, for years, Contra units had gone on bloody rampages through Nicaraguan

border towns, raping women, torturing captives and executing civilian

officials of the Sandinista government. In private, Reagan referred

to the Contras as "vandals," according to Duane Clarridge,

the CIA officer in charge of the operation, in his memoir, "A Spy

for All Seasons." But in public, the Reagan administration attacked

anyone who pointed out the Contras' corruption and brutality.

The Contras also proved militarily inept, causing the CIA to intervene

directly and engage in warlike acts, such as mining Nicaragua's harbors.

In 1984, these controversies caused the Congress to forbid U.S. military

assistance to the Contras -- the Boland Amendment -- forcing the rebels

to search for new funding sources.

Drug money became the easiest way to fill the depleted Contra coffers.

The documentary evidence is now irrefutable that a number of Contra

units both in Costa Rica and Honduras opened or deepened ties to Colombian

cartels and other regional drug traffickers. The White House also scrambled

to find other ways to keep the Contras afloat, turning to third countries,

such as Saudi Arabia, and eventually to profits from clandestine arms

sales to Iran.

The secrets began to seep out in the mid-1980s. In June 1985, as a reporter

for the Associated Press, I wrote the first story mentioning Oliver

North's secret Contra supply operation. By that fall, my AP colleague

Brian Barger and I stumbled onto evidence that some of the Contras were

supplementing their income by helping traffickers transship cocaine

through Central America. As we dug deeper, it became clear that the

drug connection implicated nearly all the major Contra organizations.

The AP published our story about the Contra-cocaine evidence on Dec.

20, 1985, describing Contra units "engaged in cocaine smuggling,

using some of the profits to finance their war against Nicaragua's leftist

government." The story provoked little coverage elsewhere in the

U.S. national press corps. But it pricked the interest of a newly elected

U.S. senator, John Kerry. A former prosecutor, Kerry also heard about

Contra law violations from a Miami-based federal public defender named

John Mattes, who had been assigned a case that touched on Contra gunrunning.

Mattes' sister had worked for Kerry in Massachusetts.

By spring 1986, Kerry had begun a limited investigation deploying some

of his personal staff in Washington. As a member of the Senate Foreign

Relations Committee, Kerry managed to gain some cooperation from the

panel's Republican leadership, partly because the "war on drugs"

was then a major political issue. Besides looking into Contra drug trafficking,

Kerry launched the first investigation into the allegations of weapons

smuggling and misappropriation of U.S. government funds that were later

exposed as part of North's illegal operation to supply the Contras.

Pau